I have read several articles over the past year that include some harsh criticism of corporate stock buybacks. Most include a version of the argument: “President Trump’s tax cuts went primarily to wealthy Americans and corporations. Corporations squandered this windfall with stock buybacks to pump up their own stock price.” This sentiment is a little off-the-mark, but I understand the impulse. So I wanted to take a minute to work out the details on why stock buybacks are not so bad.

Uses of Corporate Cash

So say I’m a public company, and I make some money selling goods or services. What do I do with it? Here are my options:

- Pay it out to my owners through dividends

- Invest in new property, equipment, capital projects, or in other companies with a merger or acquisition

- Keep it on hand, waiting for a later investment opportunity

- Buy shares of my own stock

We’ll ignore #3, because it really boils down to, “wait a bit and then do #1, #2, or #4”. Most of the negative stuff that’s been written about stock buybacks is based on the idea that companies, with fresh cash on hand due to the 2018 tax cut, ought to be doing #2. Drew Hansen’s article in Forbes, By Tripling Its Stock Buybacks, Apple Robs Workers and the Economy, is a good example of this type of criticism. This is misguided for a few reasons. But first, a quick sidetrack on stock buybacks versus dividends, and why they are close to the same thing most of the time.

Stock Buybacks are Very Similar to Dividends

Both stock buybacks and dividend payments are simply ways for firms to pay money to their ownership (shareholders). If you personally own a small business, you probably consider this to be a pretty important part of the whole process. After employees and vendors have been paid, future investments have been invested, acquisitions have been acquired, and taxes have been taxed, you want to get paid!

If you are the sole owner, you can cut yourself a distribution check. If you are a public firm, you can declare a dividend for the benefit of your public ownership. Or alternatively, you can call a stockbroker, and ask to buy shares of your own stock. This reduces the number of publicly owned shares. It also benefits shareholders by a combination of 1) paying cash for shares and/or 2) slightly raising the per-share price of the shares that aren’t specifically bought. This effectively distributes the cash from the corporate treasury to the pockets of shareholders (just like a dividend).

The two processes are so similar economically, that corporate finance professionals spend a lot of time sussing out the finer details of which method would be a more efficient path to the same end– returning cash to ownership. There are a few differences in terms of investor expectations and tax treatment for shareholders, which are not important enough to get into here. The important thing to remember is that dividends and share repurchases are two fundamentally similar ways to take cash from inside the firm and put it in the hands of ownership, or shareholders.

So What’s So Bad About Paying Shareholders?

Let’s go back to what I see as the central criticism against share buybacks: The idea that companies ought to invest in themselves– building infrastructure, factories, and new offices. They should not pay out shareholders through share buybacks. This rings true! I think we all tend to see corporate owners as monocle-wearing, top-hatted capitalist scrooges bent on stomping on the American worker.

But let’s step back and look at this in light of the full American public market for project-funding money. In a market economy:

- Firms seek investment opportunities and try to earn profits using their employees’ expertise and the assets they own.

- They have owners (shareholders) that expect a certain annual return on their investment.

- The riskier an owner perceives the firm’s business activities to be, the higher annual return they will demand.

So firms are constantly evaluating each investment opportunity against a baseline of their owners’ demand for performance. If shareholders expect to earn $10 per year for every $100 they have invested in the company, firms will only invest in projects that can beat that hurdle. Projects that don’t earn more than a 10% return will be scrapped. And if there are not enough hurdle-beating projects “on the table”, then they will follow their fiduciary duties to shareholders and return the cash to the ownership of the firm.

Let’s Do A Little Model

Let’s make this more concrete. Say the entire American economy consists of two firms, Safe Inc. and Risky Inc.

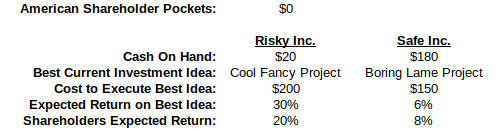

Safe Inc. is big and established and grows a little bit every year. Risky Inc. is a fast-moving startup that has a lot of interesting ideas but very little cash on-hand and bad credit. Here’s what we look like:

Safe Inc. has earned some profits and now has $180 in cash on hand. Unfortunately, they don’t have any really great ideas for what’s next. Their best idea doesn’t quite measure up to their shareholders’ expectations of what a project needs to earn. On the other hand, Risky Inc. has a great idea but no money to execute it with.

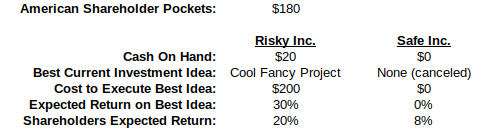

The key is that in our miniature economy, American shareholders probably own shares in both companies, for diversification. So, let’s say Safe Inc. correctly decides that their best idea doesn’t meet their shareholders’ expectations. They decide the best use of their cash is to pay it out with a dividend or stock buyback. They decide to go with a stock buyback, and use cash from the corporate treasury to buy a few shares from each individual stockholder. The company loses cash, shareholders gain cash, and the value of a share of Safe Inc. goes up a little bit. Here’s where we are now:

How Money Finds Its Way to the Best Projects

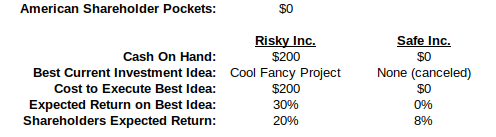

Now things are looking up for Risky Inc. They still don’t have money to execute their great idea, but now American shareholders have money in their pockets. So Risky Inc. can go to Wall Street and ask investors for equity financing for their new project. American shareholders are happy to invest in Risky Inc. They still have a need to save and invest the $180, because hiding all that money under the sofa is a bad idea. They just need someone to take their money! So American shareholders invest all $180 extra dollars in Risky Inc.’s new equity project. We end up with:

Now Risky Inc. has the cash to execute their great project idea. They’re going to go build facilities, hire additional employees, and earn money for their shareholders. Stock buybacks were the mechanism that drove beneficial investment! This is how to look at stock buybacks, and indeed the whole system of American market capitalism. Our economy is self-organized to funnel resources to the firms with the best, most profitable, most dynamic projects.

One last note– look back at the initial state of our miniature American economy. Safe Inc. could have invested in their crappy project– they had enough cash to execute. But that would have been very bad for everyone in the whole economy!

It would have been easy to criticize Safe Inc.’s greedy CEO and Board of Directors for paying out shareholders instead of investing in their company. But by making the responsible decision to forego their relatively weak project and return money to shareholders, they created the possibility for the overall system to develop a much better project that has the potential to create much more economic activity. That’s why stock buybacks aren’t evil.

Discover more from Luther Wealth

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Reply to “Stock Buybacks Aren’t Evil”