For the past month I’ve been working on a few improvements to the asset allocation model that underpins my portfolio management process at Luther Wealth. I’m really proud of the models currently in place, but I like these new ones even better! I’ve been able to fix some blind spots, and I’ve also been able to avoid some structural problems with one of the equity index funds I have been using. None of these changes are mind-blowing, but I’m proud to work constantly to make small, incremental improvements to my portfolio management process.

Some Reasons I’m NOT Updating the Model

I’m not updating the model as a result of the 2024 election. I’m not updating it because of where the stock market is sitting currently. I’m not updating it because of tariffs. My portfolio models are designed to be appropriate in a wide variety of market environments. They are designed to offer an investor of a given risk-appetite a good mix of expected portfolio returns for a given level of expected portfolio risk. In other words, I don’t have a model for good markets and a model for bad markets.

So why am I updating my portfolio models?

A Few Things I Wanted to Improve in the Old Model

I’m really proud of the current asset allocation model I’ve developed at LWM. Of all of the various aspects of being a financial adviser, portfolio management is the area I’m the most comfortable and confident in. The allocation model was the first piece of the puzzle I put together, and its worked very well for me for the first few years serving clients.

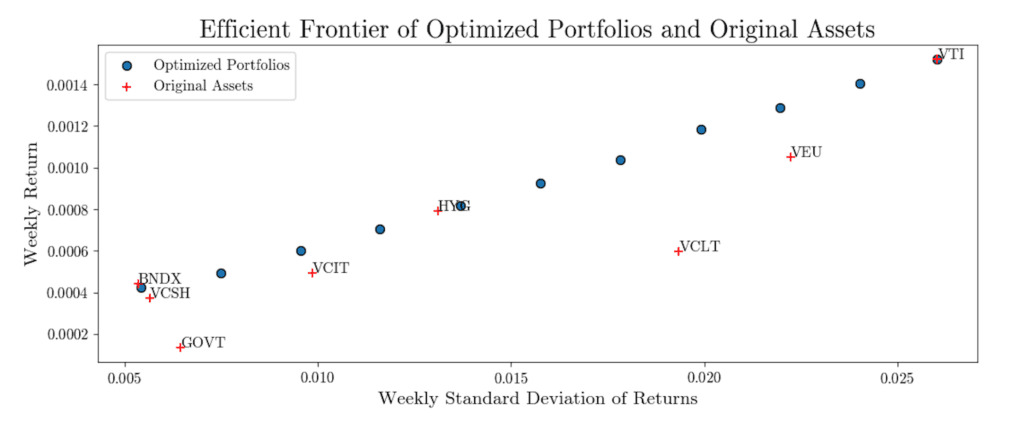

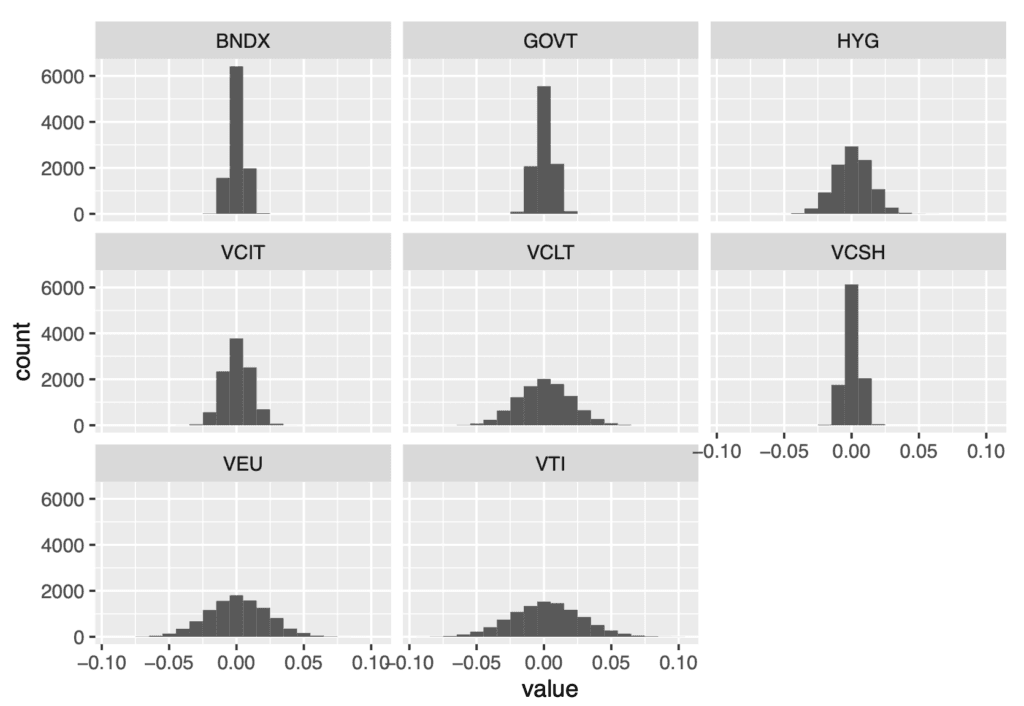

However, there’s always room for improvement. First off, the current model doesn’t include US government bonds. All of the investment grade exposure in the model comes from VCLT, a long duration corporate bond ETF. This causes an additional problem because there is no US short or medium duration fixed income exposure in the model. This is an important flaw, because the lowest-risk piece of the model is riskier than it could or should be.

Additionally, the model does not include any foreign bond exposure. These three flaws, taken together, make the fixed income part of the model weaker than I would prefer. These weren’t oversights at the time– there were some tradeoffs between comprehensiveness and lookback period that had to be made. The more comprehensive the asset coverage, the more you have to rely on newer ETFs that have less pricing history.

Over time, I’ve found some ETFs that meet both goals a little better, and this has led me to add GOVT for government bond exposure, VCIT and VCSH for full corporate bond coverage, and BNDX for foreign bond coverage.

A Structural Reason to Abandon VTWO

Up until now, I have used the combination of VONE and VTWO for the bulk of my core equity allocation in my models. VONE is a low fee ETF tracking the Russell 1000 (large and mid-cap) index, and VTWO is a low fee ETF tracking the Russell 2000 (small cap) index. However, I’ve decided to simplify the core equity allocation to just use VTI instead (tracks the full domestic equity market, all capitalizations).

Sticking with market cap weightings

First, any reasonable allocation split between VONE and VTWO will result in a massive overweight of small cap stocks versus market cap weightings. For example, the biggest constituent of VTWO is Sprout’s Farmers Market (SFM) at 0.57%. In VTI, SFM is only 0.03%. So if you try to index the entire domestic stock market with a 90/10 mix of VONE and VTWO, you’ll still have almost double the correct allocation to SFM. As a rough approximation, any allocation to small cap stocks over 5% is probably massively over-weighting small caps in your portfolio. At least relative to market cap weights.

Structural front-running problems with the Russell 2000 index

The predictability of index fund trading, particularly during events like the Russell 2000’s annual reconstitution, creates opportunities for “front-running.” This involves sophisticated traders anticipating the buying or selling activity of index funds and strategically positioning themselves to profit from it. Knowing that a Russell 2000 tracking fund must purchase certain stocks being added to the index, these front-runners will buy those stocks before the fund does, driving up the price. When the index fund then buys the stock to match the index, it’s forced to pay the inflated price, effectively transferring wealth from the index fund (and its investors) to the front-running traders. The same principle applies in reverse for stocks being removed from the index; front-runners will sell before the index fund, driving the price down and allowing them to buy back at a lower price after the index fund completes its sale.

This front-running isn’t necessarily illegal, especially in the context of index reconstitution. It’s a form of arbitrage, exploiting the predictable behavior of passive investment vehicles. High-frequency trading (HFT) firms are particularly well-equipped to engage in this type of front-running, using sophisticated algorithms and rapid execution speeds to detect and capitalize on these opportunities before other market participants. The annual Russell Reconstitution in June is a prime example, where the changes to the index composition are known in advance, creating a concentrated period of predictable trading activity.

This behavior is especially problematic for funds tracking the Russell 2000 index, because there is more money tracking the small cap Russell 2000 versus the large cap Russell 1000. Normally, there wouldn’t be much front running benefit surrounding a downgrade of a ticker from the large cap index into the small cap index. Forced buying by the small cap indexers should roughly equal forced selling by the large cap indexers. But the Russell small cap index is much more popular than the Russell large cap index. For example, a lot of investors hold an S&P 500 index fund for large caps and a Russell 2000 fund for small caps. Less money tracking the Russell 1000 means that stocks moving out of the Russell 1000 index into the Russell 2000 index mostly involves Russell 2000 money flowing around.

The impact of front-running on Russell 2000 index funds can be significant. It increases the fund’s transaction costs, reduces tracking accuracy, and ultimately detracts from investor returns. While transparency in index methodology is generally seen as a positive, in this case, it inadvertently provides ammunition for front-runners. Some argue that this cost is unavoidable, suggesting that without arbitrageurs, the price movements caused by index fund trading would simply occur on the effective date and potentially be even larger. However, the consensus remains that front-running represents a real and persistent challenge for investors in Russell 2000 tracking funds.

The New List

All that said– my latest model will utilize the following ETFs for the core portfolio:

- VTI – core domestic equities, all capitalizations

- VCSH – short term domestic investment-grade corporate bonds

- VCIT – medium term domestic investment-grade corporate bonds

- VCLT – long term domestic investment-grade corporate bonds

- GOVT – domestic government bonds

- BNDX – foreign bonds

- VEU – foreign market equities

- USHY – domestic high yield bonds

What does this mean for current clients?

I won’t be shifting around any current client investments based on this model change. I still think the previous model works well, and I don’t want to generate any unnecessary realized taxable gains in client portfolios. But in most cases, I’ll be using the newer model to guide future investments, to slowly let client portfolios evolve towards the new model recommended ranges.

Discover more from Luther Wealth

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.